Sign up to our newsletter Back to news

How are female essential workers faring amidst COVID19?

The health and essential workforce has emerged as an indispensable backbone of the economy today, and much of the conversations surrounding labour reforms and protection have the plight of these workers at their core. As this workforce around the world is being lauded as warriors fighting a novel threat, the search for sex-disaggregated data of these frontline workers reveals remarkable information about the impact of the virus. 70 percent (around 100 million females) of the world’s health, social, and care workers are women who are on the frontline, attempting to mitigate the outbreak and ease the burden of isolation on the larger population.. . They are also further burdened with care work that the COVID crisis has exacerbated – pre-COVID, women performed a daily average of 4 hours and 25 minutes of unpaid care work against 1 hour and 23 minutes for men. The disproportionate number of essential and informal workers that are women reflects in the disproportional impact of the virus.

What do COVID19 case numbers tell us?

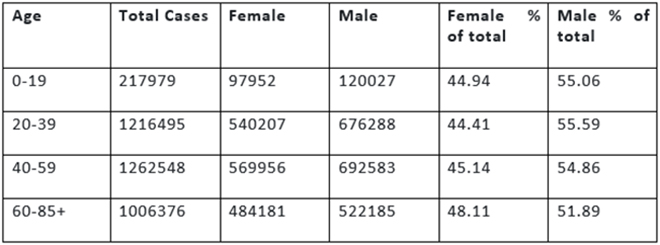

Countries have not made a rigorous and sustained enough effort towards collating periodic and consistent sex-disaggregated data of COVID19 cases and deaths. UN Women’s 24th June report on COVID19 and emerging gender data only had gender-based data for 44 percent of reported cases, and the data was based on reporting from 125 countries, areas, and territories. Amongst these cases, 45.7 percent were female, and 54.3 percent were male. Based on the data in the report, table 1 shows the age and sex disaggregated data for all reported cases that have gender-segregated data:

Table 1: COVID-19 cases, by age and sex (June 24th)

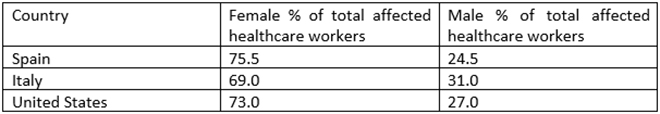

The same report showed the following sex-disaggregated percentage of healthcare workers affected in Spain, Italy, and the United States:

The same report showed the following sex-disaggregated percentage of healthcare workers affected in Spain, Italy, and the United States:

This data reveals that among the selected cases, though men are affected more in terms of overall coronavirus cases, the percentage of women healthcare workers affected is far higher, cementing the correlation between higher numbers of female essential workers resulting in higher numbers of cases amongst them. A New York Times analysis of census data crossed with the federal government’s essential worker guidelines revealed that one in three jobs held by women has been deemed essential, as compared to 28 percent of working men. These guidelines, accepted by most of the states, suggest that the sectors of energy, child care, water and wastewater, agriculture, critical retail (groceries, hardware), critical trades (electricians, plumbers), transport and social service should be deemed essential, and its workers given the priorities required with the designation. These designations, while important to determine avenues of work and productivity during a crisis, also determine the statistics on the COVID cases scoreboard.

The Plight of the informal health workforce in India

India has about 1.03 million Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers and 2.7 million Anganwadi workers. ASHA workers’ responsibilities include promoting immunization, creating awareness on health, and providing referrals for the health of women and children. They are the first point of contact at the local level for any health-related concern, including pregnancy-related counselling. The Anganwadi system was first set up to look over cases of malnutrition present in women and children under the Integrated Child Development Services Programme (ICDS). Anganwadi workers provide support for children and pregnant women and educate mothers on breastfeeding, nutrition for children etc. Consequently, they are in charge of distributing rations of rice and daal to young mothers and children so that they can receive adequate nutrition.

In India, the ASHA workers have benefitted the rural healthcare system tremendously, especially in the battle against malaria and leprosy. However, as they now tackle the gargantuan task put forth by COVID19, their lack of formal employee status in the health system has brought forth how severely underpaid they are. This lack of payment is compounded by the fact that their work is considered voluntary and part-time. Their work deliverables have quadrupled, since they now have to visit houses, identify potential cases, document travel details, coordinate the delivery of essential items to quarantined households, and track migrants returning home. The fact that we have vital local data required to gauge national trends is due to the work of ASHA and Anganwadi workers, who are responsible for documenting numbers. They also help pregnant women and distribute rations to them during these trying times.

Though the Ministry of Women and Child development has been guiding these workers on how to keep safe during the onslaught of the coronavirus, through online sessions, this effort has been limited due to lack of access to internet and digital devices. These informal workers are also struggling with the lack of protective gear. ASHA workers, for example, are not positioned in the same level as formal health workers when it comes to profiling for protective gear. They are characterized as low-risk workers, according to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s guidelines on ‘Rational Use of Personal Protective Equipment’ , as compared to other workers, and thus recommended to have only triple layer masks and gloves for their protection. Since the community health workers are the first line of defence against the virus, this differentiation seems arbitrary and unreasonably risky.

Community health workers are also fighting the prejudice that comes with being in the frontlines; the rising fear and paranoia surrounding the virus has caused citizens to deny health workers entry into their homes, coupled with violent attacks and harassment. Doctors and nurses around the world are hailed as superheroes and lauded in balconies, while these informal workers are being deprived of equally deserved respect and gratitude.

Essential and informal health workers must be brought within the ambit of formal healthcare and provided the same benefits and protection in order to explicitly appreciate and account for the tremendous tasks they have been performing during this crisis. COVID19 has clearly exposed the double burden in care work and essential work that women are undertaking, resulting in physical and emotional duress. COVID19 has no gender – its impact should be gender agnostic as well. A focused redistribution of work is in order so that differences in experiences do not result in inequality in management and treatment.

Dharika Athray is a Research Intern, ORF Mumbai

Aditi Ratho et Dharika Athray (ORF)

14 July 2020

Comments :

- No comments

Post a comment